In the midst of our urban landscapes, dotted with glass-clad skyscrapers and sleek modernist designs, there exists a style that evokes strong reactions, both of admiration and critique. Brutalism, a movement that flourished from the 1950s to the mid-1970s, remains one of the most polarizing styles in architecture and urban planning. Characterized by its stark, geometric forms and extensive use of raw concrete, Brutalism has been both lauded for its honest expression of materials and structural elements, and criticized for its perceived coldness and imposing presence. This blog post delves into the essence of Brutalism within urban planning and public spaces, exploring its origins, characteristics, significance, and the evolving perception of this bold architectural style.

Brutalism Unveiled

Introduction to Brutalism

Brutalism in architecture is often synonymous with the use of stark, raw concrete and imposing structures that stand as bold markers in urban landscapes. Yet, the essence of Brutalism extends far beyond its rugged exterior to a profound philosophical foundation. This movement, emerging in the mid-20th century, represents a radical departure from traditional architectural aesthetics, focusing on honesty, functionality, and the raw beauty of materials.

The Genesis of Brutalism

The term “Brutalism” originates from the French “béton brut,” meaning “raw concrete,” a phrase popularized by the architect Le Corbusier. This term was emblematic of Le Corbusier’s approach in his Unité d’Habitation project, which celebrated the unadorned aesthetic of concrete. This marked a pivotal moment in architectural history, with concrete becoming the material of choice for Brutalist architects, symbolizing strength, durability, and an unflinching honesty in design.

Philosophical Underpinnings

At its core, Brutalism was a reaction against the frivolous and ornamental trends prevalent in mid-20th-century architecture. It championed a stripped-back approach, where the focus was squarely on the building’s function, structure, and the honest expression of materials. Pioneers of the movement, including Le Corbusier, Alison and Peter Smithson, and Ernő Goldfinger, viewed Brutalism not just as an architectural style but as a means to foster social progress through direct, functional, and unpretentious design.

Brutalism and Urban Planning

Brutalism’s influence extended into urban planning, where its principles were applied to create spaces that prioritized social interaction and community life. Brutalist architects envisioned their buildings as integral parts of the urban fabric, designed to be both functional and inclusive. This was evident in the design of public buildings, housing complexes, and communal spaces, which often featured expansive open areas, modular designs, and a seamless integration with their urban surroundings.

Explore 7 ways to navigate crowded spaces and gaining personal space. Visit Finding Your Breathing Room – 7 Ingenious Ways to Navigate Crowded Spaces and Maintain Personal Space.

Delving into the Defining Traits of Brutalist Architecture

Brutalist architecture, with its distinctive approach and aesthetic, offers a striking departure from conventional architectural designs. This style, emerging prominently in the mid-20th century, is characterized by several key features that make Brutalist buildings stand out in the urban landscape. Each of these characteristics not only defines the visual identity of Brutalist architecture but also reflects the underlying philosophies of the movement.

- Monolithic Presence: One of the most recognizable aspects of Brutalist architecture is its monolithic and blocky appearance. These structures often present as massive, singular entities, giving the impression of being carved from a single block of material. This monolithic quality contributes to the sense of permanence and stability that Brutalist buildings convey. The rigid geometric style, characterized by stark, angular forms and a lack of ornamentation, underscores the movement’s emphasis on simplicity and functionality.

- Raw Materiality: The emphasis on materials is a hallmark of Brutalist architecture. Unlike styles that cover structural elements with decorative facades, Brutalism celebrates the raw, inherent beauty of its construction materials. Concrete, with its rugged texture and solid form, is the most commonly associated material with Brutalism, often left unfinished to display its natural state. This “béton brut” (raw concrete) approach allows the material’s organic imperfections and varied textures to become a focal point. However, Brutalism also incorporates other materials like steel and glass, which are used in a manner that highlights their intrinsic qualities rather than disguising them under decorative treatments.

- Modular and Prefabricated Elements: Repetition and modularity are significant elements in Brutalist architecture, reflecting the movement’s inclination towards efficiency and functionality. Many Brutalist buildings feature repetitive modular elements, creating a rhythm and uniformity that is both practical and aesthetically coherent. The use of prefabricated structures is also common, aligning with the movement’s principles of economy and mass production. These prefabricated components not only expedite the construction process but also embody the Brutalist ethos of straightforward, unadorned functionality.

- Engagement with the Environment: Despite their imposing presence, Brutalist buildings are often designed with a keen awareness of their surrounding environment. Architects of Brutalist structures typically employ rugged, landscape-oriented designs that seek to integrate the building into its context. This might involve adapting the building’s form to the natural contours of the landscape, creating interactive outdoor spaces, or using materials that resonate with the local environment. This consideration ensures that Brutalist buildings, despite their scale and materiality, maintain a dialogue with their surroundings, often enhancing or complementing the urban or natural landscape.

The characteristics of Brutalist architecture—its monolithic forms, raw materiality, modular repetition, and environmental integration—collectively encapsulate the essence of the movement. Far from being merely austere or imposing, Brutalist buildings embody a deep-seated philosophy of honesty, functionality, and social utility. By understanding these defining traits, we gain insight into the intentions behind Brutalist designs and appreciate the enduring impact of this bold architectural style on our urban landscapes.

In addition to learning about the Brutalism Architecture, delve into another famous building. Visit Discovering the Oculus Center – A Modern Marvel of Innovation and Design.

Explore the Elegance of Four Characteristics of the Renaissance Architecture. Visit Exploring Elegance – The Four Defining Characteristics of Renaissance Architecture.

Discover the Difference between the Renaissance Revival and Italianate Architecture in New York City. Visit Unveiling the Distinct Charm of Renaissance Revival vs. Italianate Architecture in New York City.

The Role of Brutalism in Shaping Urban Spaces and Public Life

Brutalism, with its distinctive architectural language, has played a significant role in the development of urban spaces and public buildings during the mid-20th century. Its application in urban planning and the design of public spaces was driven by a commitment to functionality, social equity, and the rejuvenation of war-torn urban landscapes. This section delves into how Brutalist principles have influenced urban planning and the design of public spaces, contributing to the creation of environments that are both utilitarian and inclusive.

Reimagining Post-War Urban Landscapes

In the aftermath of World War II, many cities across Europe and beyond were in dire need of reconstruction and revitalization. Brutalism emerged as a fitting response to this challenge, offering architectural solutions that symbolized strength, resilience, and a break from the past. The robust and enduring nature of Brutalist buildings, with their heavy use of concrete and stark, geometric forms, provided a sense of solidity and permanence that was much needed in these recovering urban areas. By employing Brutalist designs, urban planners and architects aimed to convey a message of renewal and stability, laying the foundations for modernized cityscapes that could stand the test of time.

Fostering Functionality and Equality in Public Spaces

One of the core tenets of Brutalism was its emphasis on creating spaces that were functional and accessible to all segments of society. This principle was particularly evident in the design of public buildings and spaces, where Brutalism’s stark, unadorned aesthetics were coupled with a focus on practicality and user experience. Government buildings, libraries, universities, and social housing projects designed in the Brutalist style were not just structures; they were envisioned as integral parts of the community, facilitating public services and fostering social interactions. The expansive use of open spaces, communal areas, and the integration of public functions into these buildings underscored Brutalism’s commitment to egalitarian principles and its aspiration to serve the broader societal good.

Brutalism and the Modernization of Public Institutions

The adoption of Brutalism in the design of educational and cultural institutions, such as universities and libraries, reflected a broader move towards modernization and progress in the post-war era. Brutalist buildings housing these institutions were designed to be more than just functional spaces; they were meant to inspire and facilitate intellectual and cultural engagement. The imposing presence and monumental scale of Brutalist structures lent a certain gravitas to these institutions, underscoring their importance in the fabric of urban life and the pursuit of knowledge and civic engagement.

Social Housing and the Brutalist Ethos

Perhaps one of the most socially significant applications of Brutalism was in the realm of social housing. Brutalist social housing projects were conceived with the intention of providing affordable, high-quality living spaces for the working class. These projects often featured innovative designs that maximized space, light, and communal living, challenging the conventional notions of social housing and elevating the standards of living for their inhabitants. However, the success of these projects in meeting their social goals has been a subject of debate, with some critics pointing to the challenges of maintenance and the potential for these buildings to become isolated from the broader urban context.

Brutalism’s Enduring Impact on Urbanism

Brutalism’s influence on urban planning and public spaces extends beyond its distinctive architectural style. It embodies a deeper philosophical commitment to rebuilding, modernizing, and democratizing post-war urban landscapes. Through its bold forms and emphasis on functionality, Brutalism has left a lasting mark on the design of public buildings and spaces, reflecting an era’s aspirations for a more equitable and resilient urban future. As we reflect on Brutalism’s contributions to urbanism, it is clear that its principles continue to offer valuable insights for contemporary urban planning and architectural practices.

Iconic Brutalist Structures – Pillars of Urban Architectural Heritage

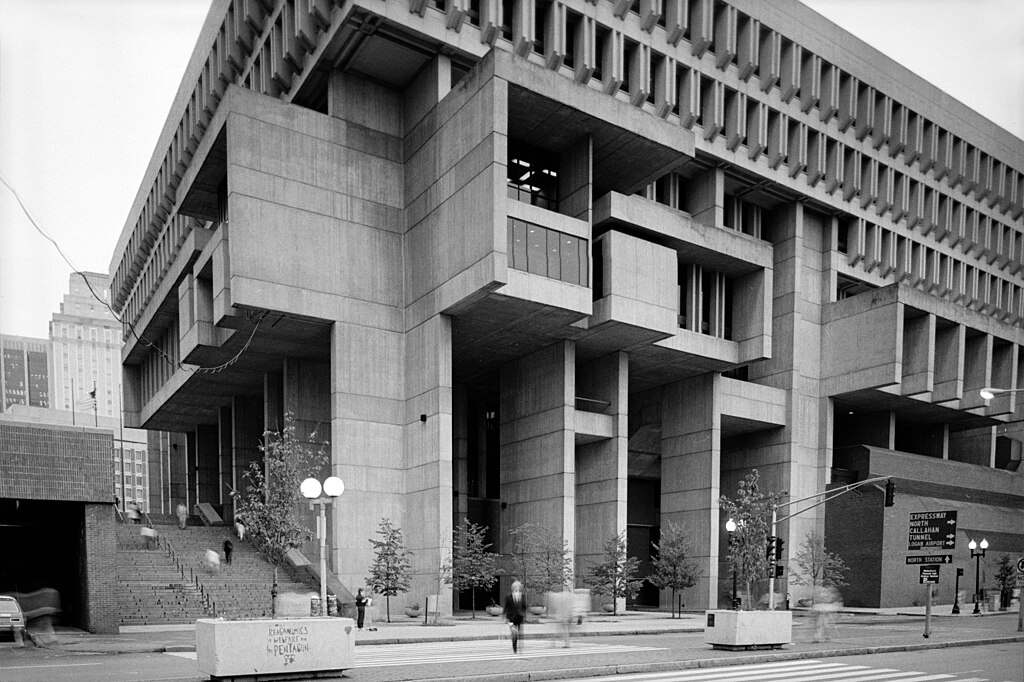

Brutalist architecture, with its distinct and imposing aesthetic, has left an indelible mark on the landscapes of cities around the world. Among the myriad of Brutalist structures, some stand out not only for their architectural boldness but also for their innovative approach to urban planning and public space design. The Barbican Estate, Boston City Hall, and Habitat 67 are emblematic examples of how Brutalism transcended mere architectural style to influence the fabric of urban life and community living.

- The Barbican Estate: The Barbican Estate in London is a prime example of Brutalist architecture’s ambition to create self-contained urban communities. Conceived in the 1950s and completed in the 1970s, this residential complex was part of a broader vision to rebuild post-war London. The Estate’s fortress-like appearance, with its towering concrete blocks, might seem imposing at first glance, but it is intricately designed to foster a sense of community among its residents. The Barbican is not just a collection of apartments; it is an “urban village” complete with cultural venues, schools, gardens, and water features. Its design intricately weaves public and private spaces, encouraging interaction and engagement among residents and visitors alike. The Barbican Centre, a cultural hub within the estate, further cements its role as a community focal point, offering theaters, galleries, and concert halls that are accessible to both residents and the wider public.

- Boston City Hall: Boston City Hall stands as a testament to Brutalism’s potential to redefine civic spaces. Completed in 1968, the building is a striking departure from traditional city hall designs, featuring a rugged, asymmetrical facade that commands attention. Its architects, Kallmann, McKinnell, & Knowles, envisioned a building that would reflect the democratic values of openness and accessibility. The expansive brick-paved plaza that extends from the City Hall’s steps serves as a vibrant public gathering space, hosting everything from protests to celebrations. This plaza, acting as a civic “living room,” exemplifies Brutalism’s capacity to create spaces that facilitate public engagement and democratic expression. Despite its controversial aesthetics, Boston City Hall continues to be a focal point of civic life in the city, embodying Brutalism’s enduring influence on public architecture.

- Habitat 67: Habitat 67, nestled on the banks of the Saint Lawrence River in Montreal, represents a bold experiment in urban housing. Designed by Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie for Expo 67, this residential complex sought to combine the advantages of suburban homes—privacy, gardens, and multilevelled spaces—with the density and convenience of urban apartments. Comprising 354 prefabricated concrete units stacked in various configurations, Habitat 67 offers its residents unique dwellings, each with its own roof garden. This innovative design challenges conventional apartment living, promoting a sense of individuality and community within a high-density structure. Habitat 67 not only stands as a landmark of Brutalist architecture but also as a visionary attempt to address the complexities of urban living and housing.

These iconic examples of Brutalist architecture—The Barbican Estate, Boston City Hall, and Habitat 67—illustrate the movement’s profound impact on urban planning and the design of public spaces. Each, in its own right, challenges preconceived notions of community, civic engagement, and urban living, offering lessons in the integration of functionality, social values, and bold aesthetics. As we revisit and reflect on these structures, their enduring presence serves as a reminder of Brutalism’s capacity to inspire, provoke, and engage city dwellers and urban planners alike.

Criticism and Controversy

Brutalist architecture, with its bold embrace of concrete and monumental forms, has stirred significant debate. Critics often point to its stark, formidable appearance as a key drawback, suggesting that the extensive use of raw concrete and the sheer size of these structures impart an oppressive or dystopian feel to urban environments. This aesthetic, characterized by an absence of ornamentation and a focus on geometric massing, has not universally resonated, with some finding it unwelcoming or cold.

Additionally, the material at the heart of Brutalist design—concrete—poses its own challenges. Over time, concrete is prone to staining, weathering, and cracking, leading to a deterioration in appearance that can reinforce negative perceptions of Brutalist buildings as dilapidated or uncared for. This aging process has further fueled criticisms, casting a shadow over the architectural integrity and appeal of Brutalist structures, and complicating efforts to preserve and maintain these iconic examples of mid-20th-century design.

The Renaissance of Brutalism – A Contemporary Revival and Reappraisal

The stark, commanding presence of Brutalist architecture, once the subject of widespread critique, is experiencing a notable resurgence in both public interest and architectural discourse. This revival is not merely a nostalgic look back but a nuanced reappraisal of Brutalism’s inherent values, aesthetic virtues, and its place within the broader narrative of architectural evolution.

Cultural and Historical Reevaluation

One of the driving forces behind the Brutalism revival is a deeper understanding of its cultural and historical context. As the years have passed, the architectural community and the public have begun to recognize Brutalist buildings as embodiments of a particular moment in history, reflecting the social, political, and economic aspirations of the post-war era. This historical perspective has led to a greater appreciation of Brutalist structures not just as functional spaces but as cultural artifacts that capture the zeitgeist of their time. Iconic Brutalist buildings are increasingly seen as landmarks worth preserving for their historical significance and their role in the architectural heritage of cities around the world.

Aesthetic Appreciation and Architectural Honesty

Alongside a cultural and historical reappraisal, there is a growing admiration for the bold aesthetic and architectural honesty that Brutalism represents. The raw, expressive use of materials like concrete, once criticized for its perceived coldness, is now celebrated for its texture, durability, and ability to age with a distinct patina. The uncompromising geometric forms and monumental scale of Brutalist architecture are being reevaluated as powerful expressions of strength and stability. This appreciation extends to the Brutalist ethos of functionality and lack of pretense, where the form of buildings is a direct manifestation of their structural and material essence.

Integration into Contemporary Design

The resurgence of interest in Brutalism is not confined to the preservation of existing structures but is also influencing contemporary architectural practices. Modern architects and urban planners are drawing inspiration from Brutalist principles, incorporating its emphasis on materiality, form, and function into new designs. This modern interpretation of Brutalism often involves a more nuanced approach to scale and human interaction, blending the style’s characteristic boldness with a renewed focus on sustainability, community engagement, and the integration of green spaces. By adopting Brutalist principles, contemporary designs aim to create buildings that are not only aesthetically striking but also environmentally responsible and socially inclusive.

Sustainability and Raw Materials

The current architectural focus on sustainability has further fueled the Brutalism revival. The Brutalist practice of showcasing raw materials in their natural state aligns with contemporary values of environmental consciousness and resource efficiency. The durability and thermal mass of concrete, for example, are being reexamined for their potential in creating energy-efficient buildings that can stand the test of time. This renewed interest in the sustainable aspects of Brutalist design principles signifies a shift towards architecture that values both form and ecological function.

Embracing Brutalism in the New Millennium

The revival and reappraisal of Brutalism reflect a complex interplay of historical appreciation, aesthetic reevaluation, and contemporary innovation. As society grapples with the challenges of urbanization, climate change, and the need for inclusive public spaces, the principles of Brutalism—honesty in materials, boldness in form, and a commitment to functionality—offer valuable lessons. This resurgence of interest in Brutalism not only highlights the enduring relevance of its architectural ideals but also underscores the dynamic nature of architectural appreciation and practice, where the styles of the past continually inform and inspire the designs of the future.

Conclusion

Brutalism in urban planning and public spaces embodies a period of architectural history that sought to express honesty, functionality, and social responsibility. While it has been a subject of controversy, the enduring presence of Brutalist structures in our cities is a testament to their significance and impact. As we move forward, the lessons of Brutalism—its emphasis on community, materiality, and structural expressiveness—continue to influence and inspire new generations of architects and urban planners. In embracing the bold and the beautiful aspects of Brutalism, we can appreciate its contributions to our urban landscapes and its potential to inform future designs that prioritize both form and function.